How Different Types of Geomagnetic Disturbances Impact Propagation

Not All Storms Are the Same

To the casual observer, a “geomagnetic storm” is just bad news for HF operators—bands go quiet, signals fade, and contacts vanish. But if you’ve been operating long enough, you know there’s more to the story.

Some storms wreck the bands. Others unlock rare propagation paths that don’t exist under quiet conditions. The trick is knowing which type of storm is hitting you—because Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) and Coronal Hole High-Speed Streams (CH HSS) behave very differently.

A coronal mass ejection (CME) captured by NASA and ESA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). (Image credit: NASA/GSFC/SOHO/ESA)

1. The Two Main Players

Coronal Mass Ejection (CME)

- Origin: Explosive release of plasma and magnetic field, often following a major solar flare.

- Arrival: Abrupt—marked by a sharp jump in solar wind speed and density, along with a sudden change in IMF Bz.

- Impact:

- Sudden HF blackouts on sunlit paths due to extreme D-layer absorption.

- Polar paths collapse almost instantly.

- Short-lived auroral propagation possible on VHF/UHF.

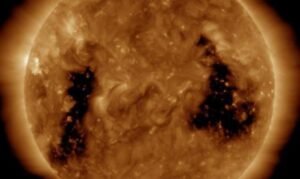

*Coronal Holes – IMAGE courtesy of NASA

Coronal Hole High-Speed Stream (CH HSS)

- Origin: Solar wind escaping through “holes” in the Sun’s magnetic field.

- Arrival: Gradual increase in solar wind speed over several hours.

- Impact:

- Extended mid-latitude auroral activity.

- Days-long periods of polar path degradation.

- Sometimes enhanced low-band DX at night due to ionospheric turbulence.

2. How They Differ in HF Impact

| Feature | CME-Driven Storm | CH HSS Storm |

|---|---|---|

| Onset Speed | Sudden (minutes) | Gradual (hours) |

| Duration | Hours to ~1 day | 2–5 days |

| High Bands (15–10m) | Often wiped out entirely | Intermittent openings possible |

| Low Bands (80–40m) | Severe absorption in daylight; quick recovery at night | Can benefit from enhanced nighttime DX |

| Special Paths | Short-lived auroral scatter; polar blackout | Persistent skew paths and mid-latitude aurora |

3. Tactical Tips for HF Operators

When a CME Hits

- Expect an HF blackout if it’s daylight in your region—don’t panic, it often lasts less than an hour.

- After sunset, check 40m and 80m for surprisingly strong regional and DX signals.

- Watch for auroral backscatter on 6m, 10m, and even 2m—these openings are rare and short-lived.

During a CH HSS

- Monitor Kp and A-index trends; polar paths often remain unusable until they drop.

- Target equatorial and mid-latitude paths for better chances at stable propagation.

- Use grayline periods to reach regions otherwise difficult during quiet conditions.

4. How to Identify Storm Type in Real-Time

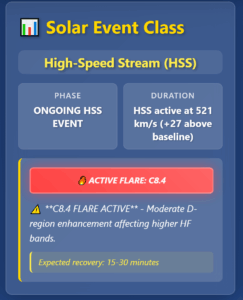

On SolarCdx.com, you can quickly spot storm type by watching the Disturbance Factor Alerts. The system automatically detects the type of Solar Event occurring and will display HSS, CH HSS, Slow Speed Stream, Quiet, etc. Also:

- HPI Gauges: A sharp jump in both hemispheres often points to a CME; slow climb suggests HSS.

- Solar Wind Speed: A sudden surge past 500 km/s is typical of a CME shock front; gradual rise over several hours indicates an HSS.

- Bz Behavior: Large, erratic swings often accompany CMEs; more consistent negative tilt is common in HSS events.

5. The Bottom Line

If you know the storm type, you can adapt your operating strategy.

- CME? Take a short break, then hunt for low-band or auroral openings.

- CH HSS? Settle in for several days of altered conditions—plan around polar blackouts and exploit grayline DX.

Tip: Bookmark the SolarCdx.com/grid so you can instantly see HPI, solar wind, and index trends—your tactical edge against space weather surprises.